There are perks to being an 8-ft.-tall canary. Everyone recognizes you and wants to be your friend. On the other hand, our world is not built for 8-ft.-tall canaries. Inside a television studio, for example, tail feathers will brush up against camera rigs. A head that high up can get awfully close to the lighting.

So it’s a good thing the world’s most famous 8-ft.-tall canary (8 and change, actually) knows his way around a set. Big Bird, his yellow plumage bright as always, his eyes ever gentle, has spent the past 50 years on one: Sesame Street debuted on Nov. 10, 1969. Its next season kicks off Nov. 16–4,935 episodes later–and the show will celebrate the milestone with a special that airs Nov. 9 on HBO and Nov. 17 on PBS. Since it started, Sesame Street has won 193 Emmy Awards, launched thousands of products and changed early education around the world. The publicity blitz accompanying the anniversary has had the cast crossing the country on a summer road trip, lighting up the Empire State Building and, on this recent morning, appearing on NBC’s Today show.

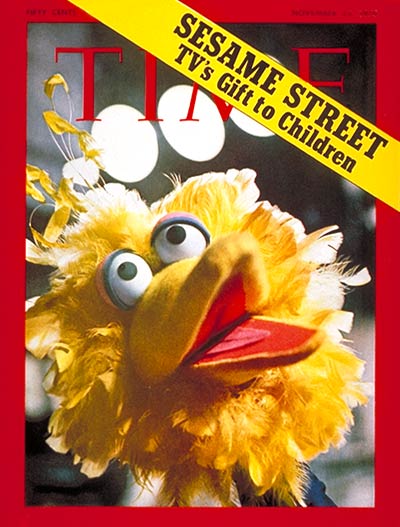

Though a helper smooths the bird’s feathers before the camera rolls, Big Bird himself is largely unruffled by the fuss. It’s not just that the fame isn’t new to him, though that’s certainly the case–he appeared on the cover of TIME in 1970, as the show marked its first birthday; led the 1985 movie Follow That Bird; has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame; and appeared with Bob Hope in the first U.S. television special ever filmed in China. More to the point, it’s hard to be excited about a 50th anniversary when you have trouble counting that high. “It’s really hard to understand numbers like that,” Big Bird told TIME between shooting Today segments. “That must be really, really, really old.”

It is, to a child. And therein lies a paradox of Big Bird: he has been 6½ years old for half a century. So to interview Big Bird is an odd, irresistible proposition. It only begins with the imagination required of any human addressing a Muppet. This one remembers things that happened decades ago, even as he has remained the child to whom his friends in the neighborhood and out there in TV land can relate. Meanwhile, the human adults who live alongside the monsters of Sesame Street have aged, and many of the children who watched the early years of Sesame have grown kids of their own.

When he sees them out in the world, Big Bird says, “they say things like, ‘I grew up playing with you’–and that makes me feel good. But I never thought about the other thing, about them growing up, like really growing up. I kind of see we’re all growing up together.”

The kids he meets today are pretty much the same as the kids he met in the past. The stuff they want to talk about is essentially the same, the feelings they feel are the same, and the qualities that made Big Bird so beloved–kindness, friendliness, open-mindedness–are as valuable as ever.

“I think all the kids I’ve met, they’ve always just been friendly and kind,” he says. “They’re looking for a friend, for somebody to play with. I think kids have been like that for all the time I’ve known them, for all my 6½ years.”

Of course, some things have changed in 50 years. The Vietnam War ended. The Berlin Wall fell. The first email was sent. When Today staffers–who you’d think would be used to all this–snap pictures of Big Bird out on Rockefeller Plaza, their cameras are iPhones. Big Bird has changed too. Caroll Spinney, the veteran puppeteer who originated Big Bird, retired in October 2018 at 84; his final recorded voice segments will air in the new season. Matt Vogel, 49, who began apprenticing with Spinney in 1996, has taken over the role.

Some changes on Sesame have come in response to data about early-childhood learning. Always meant as an educational tool, the show has been the subject of scores of studies. Some psychologists have criticized it, and even Sesame Street is not exempt from medical precautions about screen time, but other research shows educational benefits. After studies showed kids wanted more cohesive stories, Sesame Street began to shed its Saturday Night Live–like sketch structure, moving toward longer segments.

Other changes have less lofty origins. Even beyond the recurring political debates over taxpayer money going to PBS and the show–a very small fraction of its funding–the same factors that have changed the TV landscape have affected Sesame. There are more offerings on more channels, and fewer home-video sales to lean on. In 2014, Sesame Workshop, the nonprofit organization that makes the show, operated at a loss of just over $11 million; PBS children’s shows were competing for ratings with channels like Disney Junior, and even within the public-television ecosystem, shows like Curious George were beating it.

This situation contributed to what has perhaps been the biggest recent change in Sesame land: in 2015, HBO reached a deal with Sesame Workshop, for an undisclosed amount of money, to air episodes nine months earlier than they’d appear on PBS. For the fiscal year that ended in June, Sesame Workshop took in about $22.3 million in operating income, and ratings were up too. This October, it was announced that starting next season, episodes will debut on the new HBO Max streaming service.

After the 2015 deal, the set got a revamp–which critics derided as gentrification but Big Bird says he appreciated, as moving his nest into a tree made sense considering his natural habitat. The theme song got a new arrangement. The number of new episodes per year grew, and each shrank from an hour to 30 minutes, with a core arc broken into fewer pieces. In the course of that shift, Big Bird, the first nonhuman to appear on Episode 1, has become more of a side character. “I don’t really notice it because I’m always where I am,” Big Bird says, in his typical kids-say-the-Zen-est-things mode. “Wherever I happen to be, I’m always there, so it doesn’t seem like I’m ever missing.”

The newness that Big Bird is aware of has more to do with new characters on the show. In keeping with Sesame Street‘s tradition of representing the more complicated sides of life, recent additions to his neighborhood include a Muppet experiencing hunger (Lily, in 2011), a Muppet with autism (Julia, in 2015) and one whose parent was struggling with addiction (Karli, in 2019). “Meeting Julia and meeting all my other friends, I can kind of see what the world is like through their eyes and maybe feel something for them,” Big Bird says. “I’m not really sure what the word is. Empathy, maybe? I might feel empathy for somebody, and know what they feel like. I think that’s important.”

Who else might show up on Sesame Street in the future, bringing the baggage of the world, even as Big Bird remains stuck in time? Life is full of reasons a person might need empathy, and it can feel, at least for us grownups, as if the number is only growing. Sometimes, Big Bird says, kids he meets out in the world do want to talk about the scary stuff they hear grownups saying. He always has the same advice: talk to a trusted adult. But though Big Bird is only 6½, he’s often the one they want to talk to instead. “Maybe people see big 8-ft. birds a lot and they just feel comfortable,” he says. “I don’t know. I think it’s just because I’m a friendly bird.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com