Do you have a question about history? Send us your question at history@time. com and you might find your answer in a future edition of Now You Know.

Married couples may choose to celebrate their anniversaries in any number of ways, whether between themselves or among family and friends, but many couples may feel that when it comes to gifts the “rules” are a bit more defined. Paper for the first year, crystal for the 15th, silver for the 25th and so on — but where’d that tradition get its start?

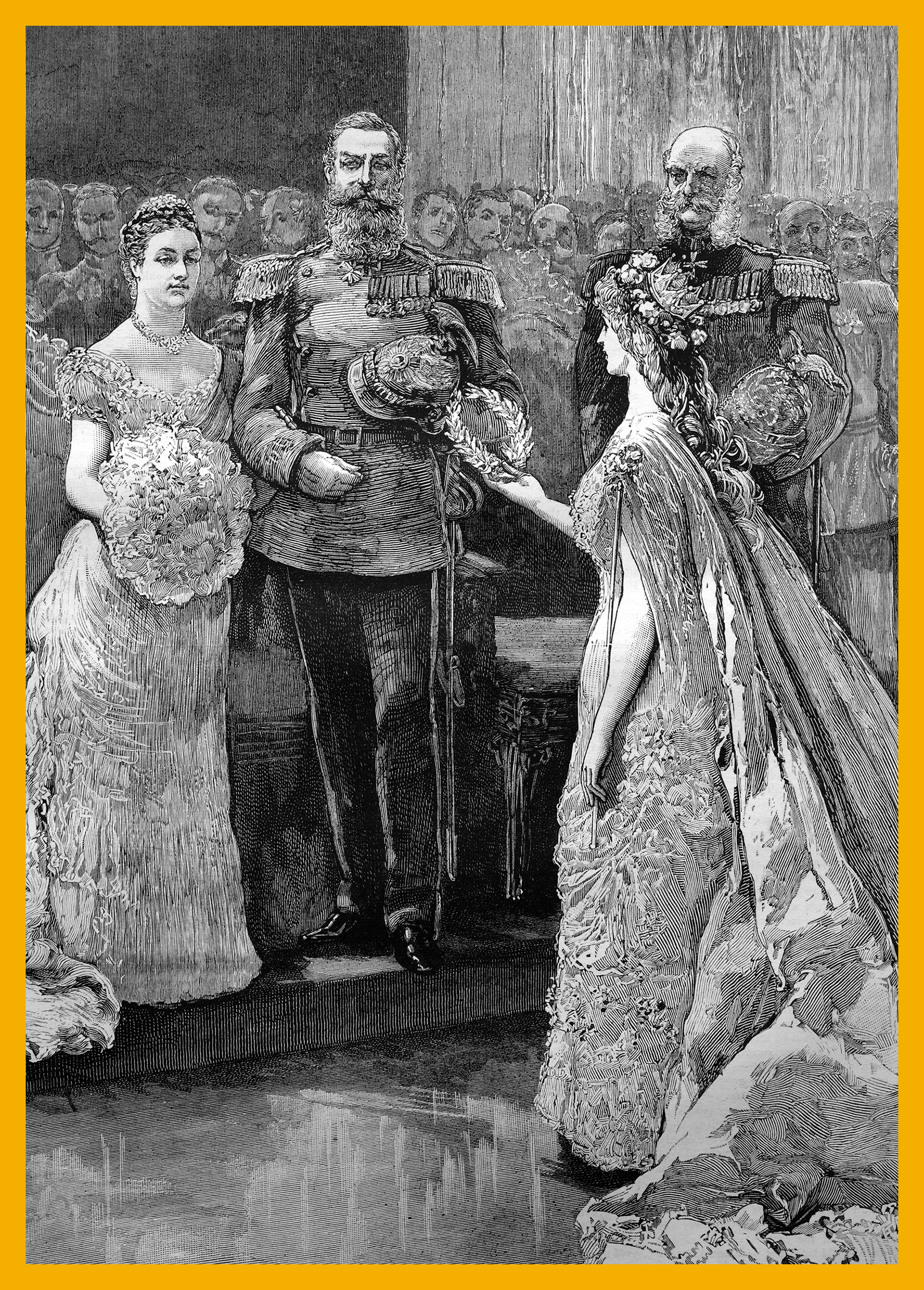

The idea of giving a gift to mark a wedding anniversary has been traced by various sources to Ancient Rome or medieval Germany, but it’s hard to come up with actual instances of anniversary presents exchanged by married couples from either society that far back. By the 18th century, however, the evidence of gift-giving in German culture is more solid. A couple’s friends might give the wife a wreath made out of silver to commemorate 25 years of marriage (the silberne hochzeit) and, should the couple reach 50 years together, a gold one later.

Among English-language regions, however, mentions of those traditions only start showing up in the 1800s. And that timing is fitting.

“[This idea] originated in the late 19th century, during the Victorian era — it makes total sense. This was a period when it became an exchange of gifts or gifts from other people, because this was the period when the love match was triumphing,” says Stephanie Coontz, Director of Research and Public Education for the Council on Contemporary Families and author of Marriage, a History. “When the love match was first invented it was very destabilizing and traditional conservatives were horrified by the idea… What in the world will we do to get people married and keep them married if love is the main reason? And so there began to be this emphasis on building a love and commitment.”

As the century progressed, media mentions of silver and gold weddings or anniversaries increased accordingly. In the earlier years, a “silver wedding” or “golden wedding” was often described as a German or Dutch tradition with which English-speaking readers would not be familiar. In 1811, for example, London’s Literary Panorama thought its readers would “hardly comprehend” the idea. When German author Marie Nathusius’ novel was translated to English in 1860, the translator added a note on a chapter about silver wedding celebrations to explain that all classes in Germany celebrated silver and golden weddings with “great festivities and rejoicings.”

Though both sides of a couple would celebrate these anniversaries — according to an 1850s travel book on Peasant life in Germany, the wife wore a silver wreath and the husband a silver buckle for the 25th anniversary — presents given to the wife were commonly emphasized. For example, the German composer Richard Wagner noted that his wife Minna’s friends presented her with a silver-spangled wreath as a souvenir of their 25th anniversary in 1861, from which she sent him a few silver leaves. And an 1843 account of a silver wedding ceremony in Germany tells of a husband giving his wife a silver crown as part of the festivities. The writer observed that, “I could not help reflecting how much such a ceremony as I have just described, contributed to keep alive the warm feelings and pure affections of youth; how genial was its influence even upon the care-worn and worldly heart.”

As Coontz explains, as the idea of the love marriage proliferated but traditional gender roles remained, celebrants began to believe that the wife’s achievement in reaching the milestone was the one worth celebrating. “There’s still not the idea that [marriage] takes work from the husband, but there’s more recognition that it takes work from the wife,” says Coontz.

Presents were one way to acknowledge that work, and indeed when the Inter Ocean Curiosity Shop for the Year 1886 answered a reader’s question about the origin of such anniversaries, the publication noted that such gifts were given not only “in congratulation of the good fortune that had prolonged the lives of the couple so many years,” but also “in recognition of the fact that the pair must have known a fairly harmonious existence” to make it so far, and that “[in] agreement with the old idea that the harmony of the household depended mainly upon the wife she received the reward.”

As the silver and gold traditions spread, celebrants — and shopkeepers — looked for parallel ways to mark earlier anniversaries too.

By 1859 edition, The (Old) Farmer’s Almanac counted off “one month from marriage makes a sugar wedding; one year makes a paper wedding” then wood at five, tin for ten, silver for 25, golden at 50, and diamond at 75. Other sources describe a “copper wedding” at twelve and a half years. By 1877, a book titled Perfect Etiquette, or, How to Behave in Society singled out eight occasions on which a specific present was appropriate. Such lists began to show up in dictionaries as well and Webster’s Complete Dictionary of the English Language, published in the 1880s, declared that gifts in the appropriate material — wooden wedding for five years, tin for 10, china at 20, the classic silver and golden for 25th and 50th, and diamond at the 60th anniversary — were given to the husband and wife on the occasion in some places. Ebenezer Cobham Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable included the same list in 1895. (Whether diamonds were given on the 60th year or the 75th remained unsettled, perhaps because 75 years of marriage required remarkable longevity, as a mention of such a celebration noted in 1862.)

It wasn’t until the 20th century that an exhaustive yearly list was invented, and even then it’s been subject to change.

“As you begin to get that sentimentalization of marriage and the nuclear family, which really comes to the fore in 19th century England and America far more than continental Europe, of course the emerging market begins to take note of it,” says Coontz. “So you’ve got Hallmark by the 1920s getting in on the act and the jewelers going ‘oh yum’ in the ’30s.”

By 1910, The Standard Home Reference Library provided a longer list of suggested names “commonly given to such anniversaries,” with yearly gifts for the first five years (paper, straw, candy, leather, wood) as well as special presents for years seven (floral), ten (tin), 12 (linen), 15 (crystal) and 20 (china). Gifts of pearl, coral, emerald and ruby filled in the roster for years 30 to 45. The diamond anniversary was acceptable either at 60 or 75 years. Emily Post’s 1922 Etiquette: in Society, in Business, in Politics and at Home, her bestselling first etiquette book, includes eight specific occasions and explained how they ought to be marked, noting that — while celebrations were often larger in Germany — in the U.S. was “not very good form” to have a big anniversary party, on the idea that such a party would seem like a gift grab. (Anniversary presents were clearly a well-accepted fact between the couple by that point.) An exception was made for the major anniversaries, as “the golden wedding [is] a quite sacred event.”

That hesitance about public celebration, however, would not last.

In fact, the very same year Post’s guide was published, the American National Retail Jewelers Association discussed supplementing the common anniversaries at their 1922 meeting.

One attendee, according to the Jewelers’ Circular, called “attention to the fact that wooden and tin anniversaries came far ahead of golden anniversaries and diamond anniversaries, and that the jeweler surely derived very little profit until after he had waited 50 or 75 years for a golden or diamond anniversary.” Over the next decade or so, the organization worked to create a uniform list for jewelers to use all over the U.S. It wasn’t all jewelry — the association considered electrical merchandise for the fifth anniversary — but there was a heavy emphasis on precious stones and and metals.

“All the marketing people and droves of sentimentalizers started figuring out reasons for symbolism and trying to make people see it as a very important symbolic step to take that brings them closer as a couple,” says Coontz.

Today such lists lists proliferate, with slight regional differences as well as modern variants on the traditional gifts — but the effort to find a suitable gift for every single year up to 50 has sometimes resulted in less obviously thrilling presents: According to the Chicago Public Library’s list, for example, the best way to celebrate 44 years of marriage was with the gift of groceries.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com